Why are some communities better at supporting entrepreneurs than others? Are some communities just destined to become entrepreneur hot spots, or are there changes a community can make to better support entrepreneurs? And who plays a role in making these changes?

There is a growing body of research looking for answers to these questions. My own journey is taking me into regions in Australia to understand who is involved and whether there are common principles that equip a region to better support entrepreneurs.

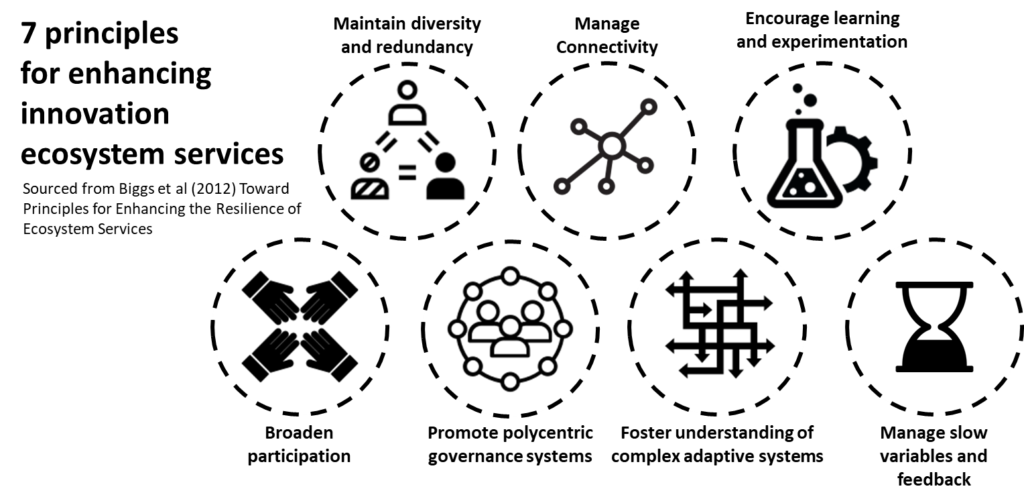

A 2012 article titled Toward Principles for Enhancing the Resilience of Ecosystem Servicesoutlines seven principles for enhancing what it refers to as ecosystem services. These principles apply broadly to both ecological and social ecosystems, and reflect insights from my recent tour of regions in Queensland. I capture the principles here to share and for input by those involved in developing entrepreneur capability in regions, as well as a record for personal reference.

Principles in an innovation ecosystem

Innovation ecosystems behave as a natural system. Unlike plants and animals, however, people are aware of the system in which they operate. We are unique in our ability to learn from feedback and make decisions to improve the system beyond our immediate self-interest.

Some principles, such as “we look after people like us” or “you have to be a local to do business with us” may seem like they support growth but can also hold a region in status quo and prevent change. Other principles can make regions more effective at supporting entrepreneurs. The assumption is that applying certain principles will help regions adapt to social and market disruptions.

The seven principles in the article may not be a definitive list, but they are captured here so others may benefit, provide feedback, and expand on the conversation. The principles can apply to any of the actors, including how government policy makers make decisions, how investors identify and manage deal flow, or how Universities develop programs and support student entrepreneurs.

My personal focus is on a specific actor in the innovation ecosystem, the innovation hub, and the role it plays in building resilience in local communities. The concept of the innovation hub is loosely applied, as it can be virtual or physical, and be represented by existing groups such as a Chamber of Commerce, University program, local government department, or passionate business leader. The aim is to provide guidance for policy makers and practitioners, and embed principles such as these into practical frameworks as part of an ongoing mapping process.

Principle 1: Maintain diversity and redundancy

Just as an ecological ecosystem requires multiple species to thrive, an innovation ecosystem requires multiple support options and as many pathways to market as possible.

Diversity includes: 1) variety (how many different elements), 2) balance (how many of each element), and 3) disparity (how different the elements are from one another). Redundancyprovides “insurance” by allowing some system elements to compensate for the loss or failure of others. Both are important for a vibrant innovation ecosystem.

Diversity can be seen in a traditional sense of different industry sectors, professions, culture and gender representation, age demographics, socio-economic bands, and political or religious beliefs. It can also be seen in the presence of diverse roles in an ecosystem, such as different types of investors, mentors, corporations, innovation hubs, and industry bodies.

Regions that have a low population density can struggle to foster diversity. Communities naturally evolve towards being the same based on safety and efficiency of shared understanding and beliefs. This creates barriers to new ideas, which can be seen as a threat.

Redundancy can be an issue in regional areas, as there may be only one actor and perhaps one individual filling a role, such as a single lawyer with startup expertise or investor with knowledge of angel investing. Specific and intentional action is needed to attract different aspects of community, where those communities feel welcome and incumbent communities do not feel threatened.

Hubs play a key role in fostering diversity through networking events and programs, often aimed at segments of the community that are less represented.

Hubs themselves can represent an under-represented aspect of the community of those who do not follow traditional business pathways. A lack of diversity in a region can result in a region not accepting a local innovation hub and providing it the support needed for it to succeed. Entrepreneurs can then leave the region as they look for communities of those who think and act more like them.

Principle 2: Manage connectivity

The article defines connectivity as “the manner by which and extent to which resources, species, or social actors disperse, migrate, or interact across ecological and social landscape”. Connectivity relates to connections across geography (between regions and national or global connections) as well as industries, age and socio-economic bands, and cultures. Connectivity, also measured as flow, can be assessed based on the structure or number of nodes and the strength of the nodes.

Connectivity is especially important for early-stage entrepreneurs with aspirations for global markets. These founders require technologies, ideas, customers, and regulation support from multiple sources and it needs to be varied, accurate, high quality, frequent, and efficient. These relationships are shared with others in the local community, building resilience to disruptions and creating pathways for others.

A region may have a limited number of individuals or organisations who can provide cross-sector or region connectivity. This can be problematic for a few reasons. First, a single-source only has so much capacity, and high demand can slow down or burn out the individual. Second, reliance on a single source can result in limited networks. Finally, a single access to external markets can result in corruption of the network where access is granted through favours or other personal bias over merit.

Hubs act as a connection node in a community, providing opportunities for “serendipitous collisions”.

They open up technical, capital, and customer networks necessary to help entrepreneurs. They also act as “boundary spanners”, creating conduits to national and global markets, diverse industry groups, and technology communities. Issues arise when competitive tension in a community results in groups attempting to own or excessively monetise connections, slowing down the flow and forcing entrepreneurs to physically leave the region to make the necessary connections instead of leveraging their local hub.

Principle 3: Manage slow variables and feedback

Building ecosystems takes time. This is contrary to political or commercial systems that are rewarded on short-term election cycles and market returns. Ecological comparisons would be measuring coal production versus rising sea levels or immediate crop yield over soil composition.

Metrics in a hub can include program participation, company formation, jobs, and investment attraction. These metrics justify ecosystem building activities but can come at the detriment of sustainable ecosystem development. For example, a local accelerator or innovation hub may create activity and investment, but the value of new entrepreneurs will leave the region as soon as the program is over without a culture and values to accept change, policies to support new businesses, and long-term community capital commitment to sustain investment.

Innovation hubs can influence long-term variables such as culture, economic development capability, and practical application of policy.

A challenge is in identifying who is accountable for the more long-term stabilising variables. Culture metrics for entrepreneurs include sentiment such as “Do I believe I can start a business in my region?” or “Do I know someone local who has started a business?” Other metrics include ease of starting a business in time and cost, access to technical or entrepreneurial talent, and infrastructure supporting entrepreneurial activity (transportation, internet, speed of personal networking). Hubs play a key role in influencing slow variables. However, they are often not adequately resourced or have the political influence to sustain the efforts required for managing long-term change and measuring and reporting on long-term impact.

Principle 4: Foster understanding of complex adaptive systems

A complex adaptive system is characterised by uncertainty, and where individual responses to that uncertainty combine to allow the system as a whole to adapt to changing environments. There is no straight path to the outcome and success can seem random and unpredictable.

We often want to reduce success to a series of steps. Models explain everyone’s role and a map of relationships. A challenge with these models is that they do not represent the changing and uncertain nature of reality and limit thinking that does not fit inside the clean boxes.

Acknowledging innovation ecosystems as a complex adaptive system can fly in the face of structured approaches to building innovation ecosystems. Many successful entrepreneurs do not participate in structure innovation programs. Participation in a startup accelerator is not guaranteed, or in some cases even likely, to result in a successful high growth company.

An innovation hub provides a culture that allows complexity to result in unexpected success.

The hub’s ability to accommodate and even encourage uncertainty can create tension from investment in the hub from government, university, corporations, or venture capital that require planned KPIs and structured programs. Other stakeholders in the community often want to see a specific model, plan, and outcomes before they will get involved. Adding process slows and limits the opportunity for variability and change, and reduce the capacity of the hub, and the region in which it supports, to adapt to change.

Principle 5: Encourage learning and experimentation

More than just personal learning by individuals, resilient region are able to learn and experiment as a community. Success is not guaranteed and failure at some point is inevitable. Learning as a community is based on what happens collectively when – not if – failure or disruption happens.

A mental model and strategy of intentional experimentation gives permission to failure and celebrates learning. It removes attachment to outcomes that can threaten identity and promote scarcity rather than abundance thinking. This is particularly critical in complex and rapidly changing environments with greater uncertainty.

The concept of experimentation and learning from failure is embedded into the core of an innovation hub.

Activities such as startup weekends and hackathons encourage the development of the “minimum viable product”. Unfinished and imperfect products are presented for customer feedback as soon as possible to refine the approach or stop continued investment. The ecosystem of investors, corporations, mentors, and researchers are intended to support the entrepreneur through each iteration. For many entrepreneurs, acceptance of failure will be a new experience in the innovation hub culture.

This culture is often in opposition to a society built around success. Resistance to failure and experimentation is indoctrinated from early school grades of “A’s” and “F’s”, employment performance reviews, and sensational media reports of low business performance. Failure as a result quickly becomes failure as an identity. The opportunity to learn and experiment is not the sole remit of an innovation hub. It needs to be embedded into community culture if it is to contribute to resilient communities.

Principle 6: Broaden participation

Participation helps tap into the collecting capabilities of the region and returns value for those involved. More than that, however, is the value to the participant from the ownership of the outcomes that comes from participation. When more individuals, organisations, and community groups participate in new ideas, transparency is improved, governance encouraged, and ideas and value grown and shared. It becomes easier to support initiatives when you have been a part of the process, and more difficult to stand aside and watch it fail when you have played an active part in its development.

Innovation hubs provide multiple opportunities for participation and shared value for most any role in the community.

Organisations can develop members and employees, individuals learn new skills, investors and corporations invest in opportunities, and more. Participation can come from early stage design to practical execution, as well as multiple levels of participation including attendance, active involvement, and personal investment.

Communities do not always take advantage of this opportunity, taking a “wait and see” approach or needing to see proof before action. This creates a self-fulfilling prophesy, where the hub can struggle if the community does not participate thereby justifying the lack of participation. Alternatively, active participation by a broad range of the community results in greater likelihood of success and encouraging more active involvement by a greater number of participants.

Principle 7: Promote polycentric governance systems

The term polycentric simply refers to multiple governing authorities at different scales. Governance is the agreed approach to decision making, including documentation, transparency, and reporting. Polycentric governance is decision making by multiple governing authorities.

Innovation ecosystems are inherently decentralised. They can be seen as a response to the slow and risk-averse centralised governance structure of institutions such as corporations, universities, and governments.

Governance in innovation ecosystems need to strike a balance between non-existent and excessive. A lack of any governance makes operations inefficient due to lack of scalability, reliance on individual personalities, and increased risk of corruption and self-interest from lack of transparency. Excessive governance can result in burdensome reporting structures, slow decision making, and poor communication from forced collaboration.

In regards to innovation hubs in regional areas, the innovation hub is not the same as the innovation ecosystem, but it can play a key role in the governance structure. If a local government or major university owns the single local innovation hub, governance may risk being centralised and limit participation and diversity. Multiple smaller organisations without a central support body can result in minimal accountability and lack of collaboration. When everyone owns the outcomes, no one is accountable.

The balance is governance without excessive control, facilitating rather than directing, organisation without bureaucracy, collaboration versus competition. This is one area in particular I am exploring to see what works, looking at models such as the Innov8 Logan or others established in response to funding such as North Queensland’s IgniteFNQ or Sunshine Coast’s SCRIPT.

Wrapping it up and applying the principles

One outcome from my research is to develop principles that can be applied by regions to better support entrepreneur development. Lists such as these provide a good reference point.

The goal is to help regions with decision making and build sustainability into the innovation ecosystem. These are lofty aspirations, and will require a broad community effort.

Your feedback is welcome. I am particularly interested in how you feel your local hub contributes to the principles, and the strength of the principles in your region.

To keep up to date and collaborate on the ongoing research, please connect with me on LinkedIn and sign up for the newsletter at startupstatus.co.