If innovation is doing something “new”, how do you know which “new” you should do?

I was speaking with a business leader about my recent thoughts on a simple definition of innovation, which is: “Something new that has value for a group of people”.

Her response was:

“I agree, but everything we do is new! We don’t seem to be getting anywhere. How do we know which ‘new’ we should do?”

The leader raised a good point. Disruptions are forcing change across all industry sectors. Like an anthill being poked by a stick, organisations can reactively respond to change by doing new things in predictable yet frantic ways.

Typical reactions to the stick of commercial pressure includes cost reductions through efficiencies or removing benefits, products, services, or staff; or increasing revenue through more sales, discounts or promotions. Activities such as these can give the sense of innovating, but can just as often be doing the same thing without adding value.

Having an awareness of what we mean by different types of innovation, where the innovation impact is applied, how the innovation process works, and why we are innovating in the first place can add value when doing “new”.

WHAT: Innovation application

One of the definitive bodies of work to define innovation type is the OSLO Manual: Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Innovation Data, which the OECD uses as a reference when comparing innovation globally. The OSLO Manual identifies four “types” of innovation:

- Product innovations,

- Process innovations,

- Organisational innovations, and

- Marketing innovations.

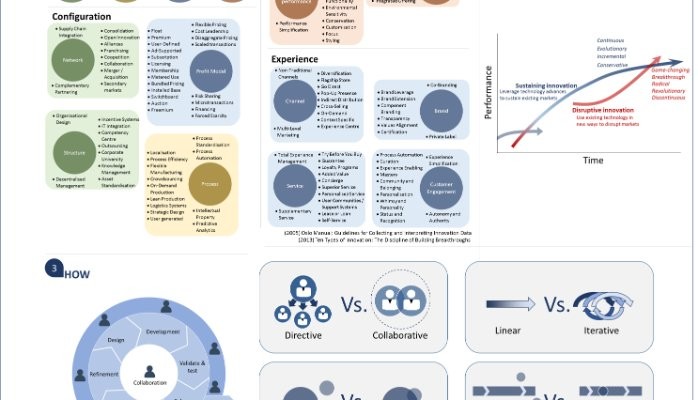

These four broad categories are useful to communicate to those starting the innovation process. When more detail is needed, Doblin’s Ten Types of Innovation provide a useful categorisation on different ways organisations can do “new”:

- Network, Process, Profit model, Structure;

- Product system, Product performance; and

- Channel, Customer engagement, Service, Brand

Doblin expands the model above to describe over 100 examples of tactics against the ten types. I have listed these tactics in the diagram below, colour coding each of the ten types of innovation against the four OSLO Manual categories:

(a larger view is available in the original post on the Sideways Thoughts blog)

Do we really need to focus on different types of innovation? A 2014 study posed a similar question when it asked “Do innovative organisations compete on single or multiple operational capabilities?”

Using data from 1,438 manufacturing plants across the globe, the researchers considered how high-performing companies developed different capabilities for innovation. Did the organisations trade one capability for another, or were capabilities approached as integrated and cumulative, developing multiple capabilities at the same time?

Their findings should not be surprising:

Developing multiple capabilities is possible and necessary for innovation performance. The trade-off model is not significantly related to innovativeness of organisations because of a narrow focus which makes the model too risky and considered damaging to an organisations’ general well-being and overall competitiveness. Linked capabilities by comparison performed remarkably well.

Organisations that compete using different capabilities or innovations in different areas are more competitive. While this might help you improve performance in your current context, another approach may be required to be resilient to large-scale disruptions.

WHERE: Innovation impact

Large-scale disruptions are consuming organisations that were only recently innovative and successful. Companies that are identified as going from Good to Great are described a short time later as “How the Mighty Fall”, or as one article put it, Good to Great to Gone. This has led to the awareness that innovation happens in different places along a continuum of two perspectives.

Examples of researchers who outline this dichotomy include:

- Michael Porter’s “continuous” and “discontinuous change,

- Tushman and Anderson’s “incremental” and “breakthrough” innovation

- Abernathy and Clark’s “conservative” vs. “radical” innovation, and

- Clayton Christensen’s notion of “sustaining” and “disruptive” innovation.

Christensen’s concept of disruption has pervaded business language due in part to the many examples of disruption we see around us in the market.

Sustaining innovations are advances that sustain established markets and often involve technology improvements. Examples include better ways to print on paper, fit more people on planes, or create smaller or faster smart phones. Sustaining innovation could be considered doing “new” things in familiar ways.

Disruptive innovations by comparison have the potential to make existing markets unnecessary. Common examples of disruptive innovations and the markets they disrupt include Uber (taxis), eCommerce (local physical stores), social media news feeds (newspaper), and on-demand music or movie services (theatres, video rentals, music stores). Disruptive innovation may not involve new technology, but is likely to use existing technology in new ways.

These two approaches are outlined in Christensen’s “The Innovator’s Dilemma”, which explains a situation similar to the natural tension for organisations to be “ambidextrous”. Established markets are rewarded for exploiting core strengths for low-risk, short-term returns. Customers demand ever-increasing quality and service at lower prices. This drives standardisation of structure and supply chains, making change more and more difficult. Initiatives that seek to explore speculative, higher-risk directions must compete for that organisation’s scarce resources that are committed to maintaining existing momentum.

This “dilemma” of change resistance creates space for smaller, more agile competition to try new approaches on less-demanding customer segments who are willing to try something new. The established market is likely to respond by fighting the new competition with current strengths (like Kodak making more efficient Polaroids to fight digital cameras) or undermining the new entrant’s advantage (such as taxis demanding regulations on Uber or combining together to monopolise the market).

The diagram above does not represent a static situation. The disruptive innovations of today become the sustaining innovations of tomorrow. Corporations such as Facebook, Apple, Google, Amazon, and IBM that at one point were the nimble disruptors now risk being disrupted.

The market is also self-learning. Progressive companies are already disrupting their own market. The Uber taxi service may be creating over 1 million jobs per year, but the company is also investing in driverless cars which will likely see a loss of those same positions in a cull of over 10 million jobs in a few decades.

HOW: The process of innovation

Like fruit from heaven, innovation is a gift sitting in all organisations. However, there is a process that can be followed so the gift can be unlocked. Innovation does not happen by itself.

Innovation is often referred to as a “light bulb moment”, but even the light bulb required electrical distribution systems and supply chains to get into every home. Successful innovation is not just a great idea, but also involves effective execution and distribution.

The process stages are commonly described as:

- Ideation

New ideas come from exposure to new ways of thinking and new experiences. Simply directing people to come up with new ideas through a suggestion box is unlikely to work if that is the entirety of your innovation program. Want a new idea? Talk to new people, experience a new culture, travel a different way to work, take on a new task, or start a new hobby. Get the brain working in new ways to get new ideas. - Refinement

Refinement determines which ideas are plausible. New ideas can be wild, untested, irrational, and not practical. This is a necessary part of the creative process. Just ask a 10 year old to design a perfect car. You get some crazy ideas. A challenge we face as adults is that we start to refine new ideas with current constraints almost as soon as they pop up. - Design

After ideas are refined and short-listed, they are designed in more detail. We create a picture of what the innovation could look like. This allows people to better envision the innovation “as if” it already existed. If you can’t see yourself in the idea or you can’t design a way for the idea to be executed, then the idea may hit the cutting room floor. - Development

Ideas that make it through design stage have resources committed to build and test. - Release

Developed ideas are released to end customers for use and validation of the value received. - Diffusion

As customers realise value, the idea is shared and diffused across additional customers, new customers segments, and possibly other industries. New ideas are generated as the innovation is normalised into a standard product lifecycle.

The process above rarely occurs in such a linear manner. Many people describe innovation where ideas are thought of, designed, developed, and tested in an iterative, fast-paced, collaborative process. Having had exposure to a wide range of organisations, I can attest that this approach can vary significantly depending on the culture in which it is applied.

The process is typically applied with considerations outlined below:

Directive vs. Collaborative

Does one person direct how innovation will be applied and what ideas will be accepted? Or is the process collaborative, including multiple employees, leadership levels, suppliers, and customers to generate, develop, and test ideas?

Linear vs. Iterative

Do each of the stages occur in a linear progression, with the idea fully designed before development and fully developed before being shown to the customer? Or is the process iterative, with ideation, design, development, and release occurring in rapid succession for immediate feedback and refinement?

Isolated vs. Integrated

Is the process isolated to one department, individual, or time period? Or is innovation integrated with business as usual to leverage the collective wisdom of the organisation applicable to practical real-world examples?

Ad hoc vs. Intentional

Is the process ad hoc, dependent on having time available or an engaged employee applying effort outside of normal work hours? Or is innovation an intentional part of your strategy, with resources allocated and leadership support?

Problem-focused vs. Future-focused

Does innovation focus on problems that need to be fixed, reactively identifying new ways to fix issues as they arrive? Or is the focus on the future, defining the best possible outcome and creating a path to that future state?

WHY: Innovation outcomes

The complex challenges facing our organisations and our species requires new thinking. Our underlying motivation will determine whether our actions will address these challenges or create new challenges that will result in our eventual demise.

Innovation is outcome neutral. “Innovative” could describe a more effective sub-machine gun as much as a cure for cancer. The same technology that facilitates payment transfers between small business owners in developing countries also allows untraceable payments that facilitate corruption and complex scams.

There is a lot of hype around innovation that allows short-term effort to return disproportionate gains, particularly in the technology start-up space. The rich are getting richer, more numerous, and more centralised. The wealth inequality gap remains systemic and pervasive, even as governments and corporations strive to remain competitive in a global market. Being wealthy is not an automatic cure for someone else being poor, as explained in the myth of trickle down innovation.

I say all this to frame my response to my leader friend who asked:

“What is the new we should do?”

Definitely look at what type of innovation we apply – to our processes, products, organisations and markets. We should consider where we are innovating, whether we are sustaining our current market or have opportunity to disrupt our market in new ways. And how we apply innovation is critical to understand the process, and culture that drives the process.

Within this framework, please consider why we innovate. Where can we make the world a better place as a result of our actions? What will make the most impact on the well-being of those we influence by our actions?

If we can answer this, then perhaps that is the “new” we should do.