You can’t throw a stick these days without hitting someone who will invent a better way of throwing sticks or redefine why we need sticks in the first place. Innovation is increasingly pervasive due to a range of converging factors, such as:

- The rapid rise of technology advances to address challenges (which are often created by the rapid rise of technology advances);

- Immediate access to large volumes of new information;

- Increased mobility of humanity leading to the sharing of information and new ideas from new perspectives; and

- Heightened awareness of the complex challenges facing humanity.

Innovation of some form is used as a verb (“We need to innovate!”), a noun (“Have you finished that innovation yet?”), and an adjective (“We are so innovative!”). Innovation is inundating our organisations, our governments, and our grammar, and for good reason. Innovation is the common prescription to get us more of what we want and less of what we don’t want.

Given innovation’s increased popularity and urgency, there is a need to ensure we have a common understanding of what we mean by the term.

What is innovation?

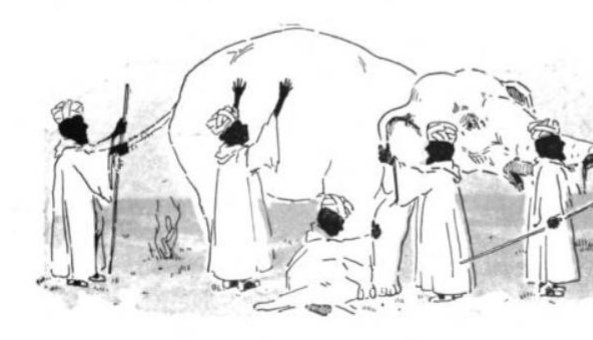

We rely on our shared understanding to make sense of an abstract concepts, similar to thoughts I previously shared about culture and strategy. Like the proverbial blind men describing the elephant, there is a risk that we can pick and choose parts of the idea without having a full picture.

How we measure a thing is inherently associated with how we define the thing. The blind man holding the tail who thought the elephant was a rope would likely use his tape measure and not worry about a scale. Another with the trunk thinking he was holding a water spout would recommend a bucket, which would be worthless to the man on the elephant’s back who was describing a throne.

How we measure something must first start with how we define it. I don’t propose to be the most enlightened of blind men, but I do use a fairly simple definition for innovation:

Something new that has value for a group of people.

Something new

First, innovation must be new. The ah-ha moment does not happen from experiencing business as usual. Innovation creates new neural pathways, breaks us out of habitual patterns, and expands opportunities.

Just how new something needs to be is up for debate. Getting more of the same by working harder or adding more people is not innovative. One hundred people doing the same thing is still the same thing. Implementing a new process to increase production using the same or fewer people is innovation. Innovation by definition is a never-ending process of doing “new”.

That has value

Innovation must be valued. There is a distinction between creativity and innovation. Creativity inspires and is important for innovation, but is difficult to measure. The very notion of measurement can inhibit creativity. Innovation by comparison has a tangible outcome that has value.

The value may not be immediately realised. Bizarre and creative creations we see on fashion runways seem to have no value, not knowing we will be wearing an iteration of that design a decade later. People strapping cardboard wings to their arms was silly, but early experiments in throwing ourselves off cliffs paved the way for the wingsuits of today.

In a similar way, education is not innovation. Learning something new is not innovation until that learning is applied in a way that can be measured. Innovation is validated learning.

For a group of people

Innovation is relative to those who are observing the innovation. Something can be innovative for one person, for a company, an industry, a community, a nation, or for humanity. We measure innovation by a range of segments such as education, health, government, manufacturing; culture groups,demographics, and nations.

Something can only be “new” once. What was innovative for a company becomes business as usual when they roll it out across the organisation. There is a difference between being able to say “We are innovative” and “We once did an innovative thing”.

This approach to innovation allows everyone to be innovative. Some groups may do a more innovative thing, while others may have a more embedded pattern of innovation. Automating our manufacturing company in the 90s was innovative for an 80-person small business, but we felt we were simply catching up to overseas companies. Sticking a bleach-filled plastic bottle into the roof of a suburban home may seem silly, but the same practice in a developing country may add hours of no-cost productive light.

A simple definition of innovation to cure insanity

We need a simple, shared understanding of innovation if we hope to have more of it. The easier innovation is to understand, the more likely it is to find engagement in leaders and those in organisations seeking change.

And really, innovation is our only hope. Einstein is attributed to the famous quote that states “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.” There is a significant need for a simple approach to finding new ways of overcoming the challenges and self-inflicted hurdles we face in organisations and society.

Even as I write this, America has experienced yet another school shooting. Without innovative thinking, we are left with responses such as expressed by Presidential candidate Jeb Bush who said“stuff happens” and to resist our impulse to act. Alternatively, talk show host Stephen Colbert’s monologue following the shooting expressed his sentiment on how new thinking is required when he shared that “one of the definitions of insanity is doing nothing and pretending something will change.”

Innovation is a cure for our collective insanity of routine acceptance.

Measuring innovation

My simplistic view is that if each person, team, and organisation did something new that added value in their community, we would see more rapid positive change. I do not mean to trivialise the complexity of change nor the significance of the challenges we experience in society and the competitive market. But sometimes the more complex the challenge, the greater the need to start with something easy to understand.

For example, we can use a basic definition to create a simple approach to measuring innovation and creating an innovation appetite.

What would it look like to regularly ask yourself and your team:

- Something new

What have you done in the past month that is different than what you have done in the past? - That has value

What value have you seen from new things you did in the past 12 months? What did you learn? - For a group of people

Who was impacted by the value, or who else was this learning shared with? Internal to the organisation? External?

The need for these questions will vary based on the nature of your team. “New” is inherent to start-up companies and newly formed teams. A culture with embedded innovation can be taken for granted as organisations mature. Before long, an established team may look back and realise they have been in a cycle of “business as usual” for some time.

I propose these three simple questions will assess the innovation appetite of yourself, your team, and your organisation. If an organisation is unable to demonstrate they are doing anything new that has value, then perhaps they have significant potential to improve their innovation capability. Aligned with an Appreciative inquiry framework, I also propose that you will affect change by simply asking the questions on a regular basis.

I encourage you to join me in exploring how we might advance more rapidly to a higher collective standard of living for every individual, team, and organisation by doing “new” to improve our situation in sustainable ways.

In the interest of creating shared value, I would be keen to hear your perspective. What is your definition of innovation and how do you measure it in your organisation?