Queensland University of Technology (QUT) announced they are winding down Creative Enterprise Australia (CEA) due to impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic. CEA is a subsidiary of QUT established in 2001 that includes a suite programs and spaces including: the Coterie coworking space, the Fashion360 accelerator and associated Stitch Lab space, the CEA Business Hub, the Collider Accelerator, the CEA Startup Fund and Creative Tech ventures Fund, the Creative3 event, and regular startup weekends.

There are understandable concerns in the Australian entrepreneur support community about the closure. Few disagree that universities face challenges as a result of COVID-19. University of Melbourne professors provide some recommendations in their post for what Australian universities can do to recover from the loss of international student fees, stating that:

Not all 38 universities will emerge from the pandemic in their current form.

To add to the conversation, I briefly look at the history and nature of university-based entrepreneur support in Australia to consider what may have already been a trend and what the future might hold. This post builds on previous posts that highlight “Why support for startups and entrepreneurs is more critical now than ever to Australia’s future” and “Opportunities for the Australian entrepreneur ecosystem through the coronavirus“.

Data comes from the mapping work on the Startup Status platform, which maps entrepreneur support organisations in Australia. There will be omissions for programs that have come and gone before tracking started and other programs may occasionally be missed. An overview of the taxonomy can be found in the initial release of the map. Feedback and corrections are always welcome.

The state of university entrepreneur support programs

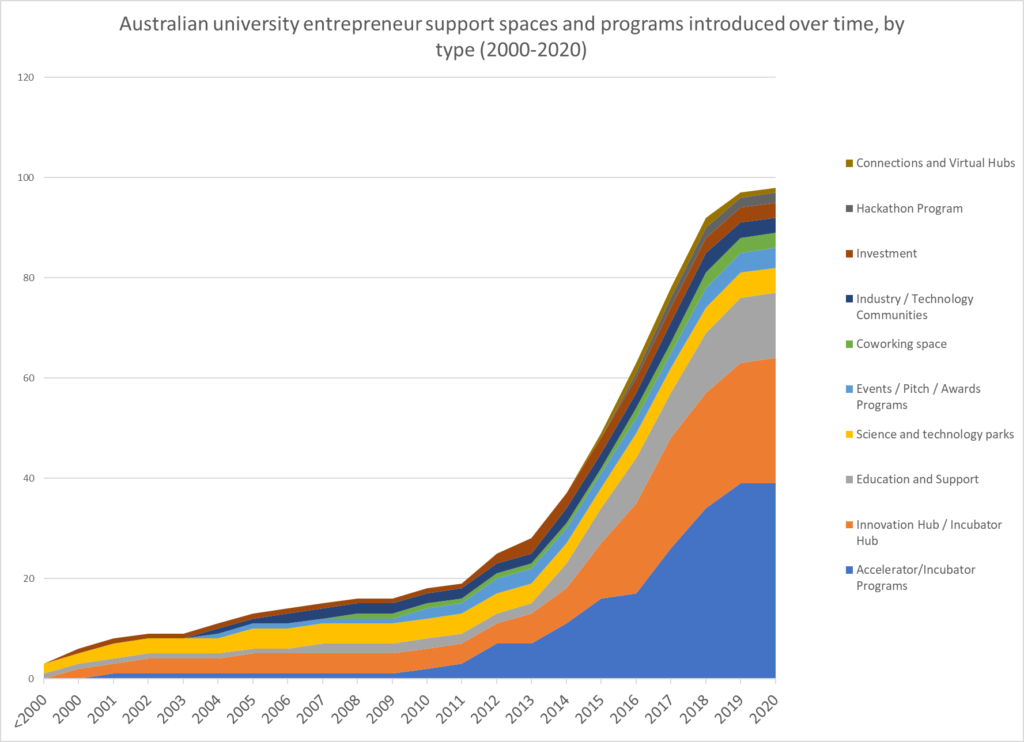

The innovation ecosystem in Australia is constantly evolving – maturing in some areas, regressing in others, but collectively advancing. The rate of increase in entrepreneur support services in Australia began to decline even before COVID-19. The total number of new university programs and spaces increased since 2010 at an average annual growth rate of 25%. The growth rate declined in 2018 to 18% and then further to 5% in 2019.

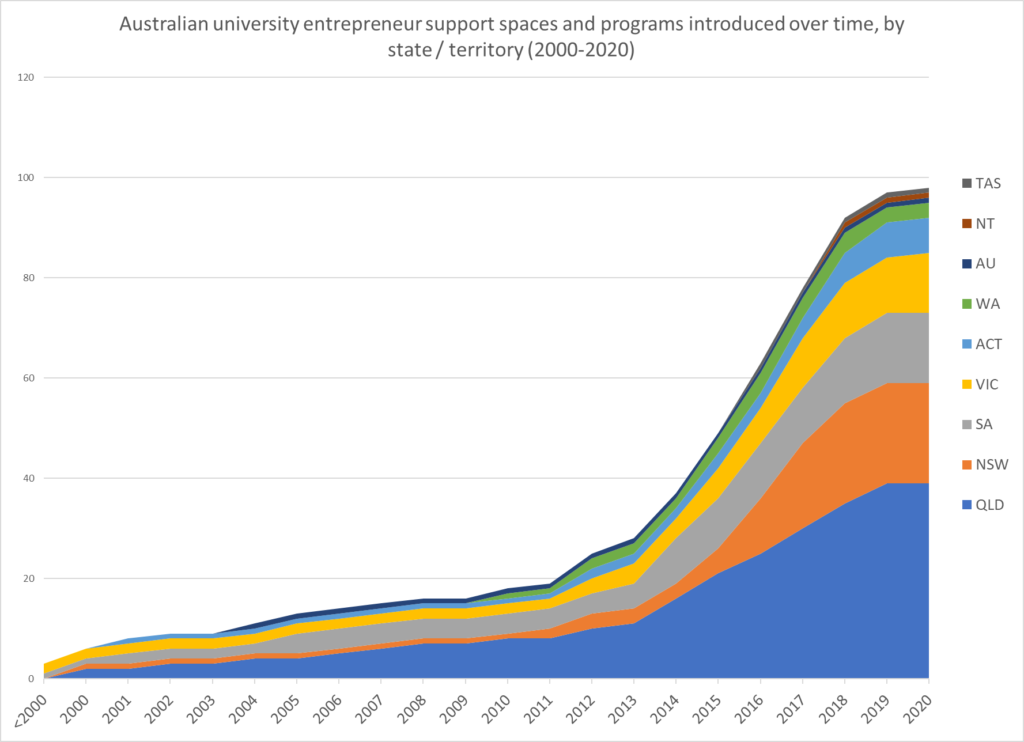

Support is provided across Australia. Queensland has a greater number of instances of programs and spaces but variations of programs are a factor. Size of programs is not accounted for, so three smaller programs may have a similar impact as one large program under one brand. There are also many cases where universities are involved in programs but are not the primary owners of the program or space. The underlying data is segmented based on one of five primary owners of the program or space: government, corporate / industry, investment / venture capital, university, or independent / philanthropic.

The data can be reviewed for each state and territory: AU, ACT, NSW, NT, QLD, SA, TAS, VIC, and WA. It is expected there will be a few programs missing, and there may be programs that may not be currently running but still listed as operational. While differences between states or territories may change slightly, the overall trend and observations from the data is not expected to change. Feedback and corrections are welcome.

The decreased rate of growth is mostly a reflection of saturation rather than performance or demand. By 2017, most universities had developed a suite of entrepreneur support services. The catalyst for growth was in part the 2015 federal $1.1 billion National Innovation and Science Agenda and subsequent support from state and local governments.

From 2018, entrepreneur support programs had begun to consolidate and specialise, while a few expanded and matured. What worked for 2015 needed to change for 2018, and the next decade into the 2020s would have already required further refinement even without the pandemic.

Creative industries entrepreneurship in Australia

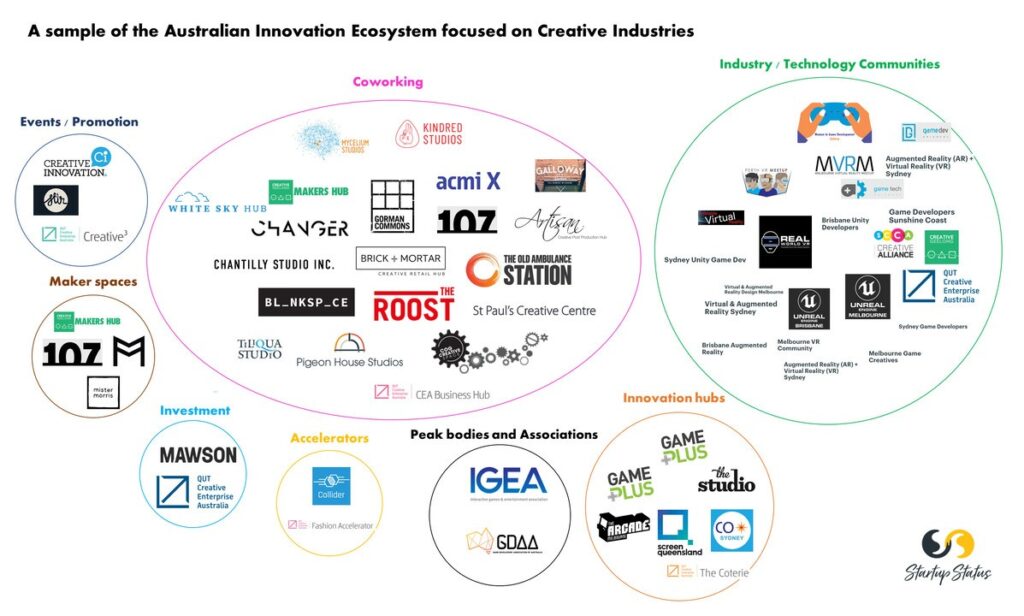

In addition to growth, another characteristic of Australia’s innovation ecosystem is its growing specialisation by industry, technology, and target markets. Ecosystem boundaries are fluid, socially defined, and there are systems in systems. CEA is part of the overall innovation ecosystem while also operating in a creative industries sub-system. These were mapped as part of a review of the creative industries innovation ecosystem in Australia in early 2019.

The more specialised the ecosystem, the more that the loss of a given actor will leave a hole. Looking at the map above, CEA was the only dedicated creative tech accelerator, one of the few options for investment, and one of the few dedicated events in Australia for innovators and entrepreneurs focused on creative technology. Diversity and density is a critical attribute of innovation support services, and the loss of a major actor such as CEA will have an impact.

The system is changing

The pandemic will stress test the system to accelerate trends, expose weakness, and remove assumed competitive advantages of size and scale or market dominance.

I reflect on a similar experience with our family printed circuit board manufacturing business impacted by the 9/11 terrorist attacks. The company started in the 1970s when there were around 2,500 PCB manufacturing companies in the United States. By 2000, the number of US-based PCB companies had decreased to 250 as a result of overseas competition. The companies that remained specialised in high-technology and low-volume production.

Our company focused on medium-volume production with off-shore capability. As a volume provider, we increased debt to support efficiency through automation and online integration. Margins were tight and there was constant pressures to reduce both cost and price. Then came the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

Like COVID-19, the immediate response was an overwhelming sense of coming together against a common enemy. The real pinch happened after about two months. Revenue from transportation, consumer goods, and telecommunications customers stopped as the country shut down. Suppliers reduced terms on already extended credit. The company balanced on the edge month by month, but eventually went into administration due to increased debt in a month where we experienced our highest number of orders ever.

Like 9/11, the COVID-19 crisis will challenge all models. Playbooks are in constant development for structures that support entrepreneur support services. It is easy to look at another economy and state what ‘should’ be done, just as there were many who offered opinion on our family business as it went under. Particularly in relation to the emerging field of ecosystem services, everyone is testing and trialling based on what works in their region and learning from others.

New models are constantly emerging. What worked in one region may not work in another and the structure of each approach can be different. Part of the new future will be the destruction of what is existing.

The challenging but needed business model

Innovation services is a challenging business model at the best of times. The majority of entrepreneur support programs are heavily subsidised. Measurement of the returns on this investment is difficult due to correlation of complex factors and transient nature of entrepreneur activity after they leave programs. Outcomes are often anecdotal at best.

Justifying this investment is a continuous fight for legitimacy. In developing business cases and feasibility studies for new hubs, a comment often shared by those initiating the project is that “we will provide the initial capital until it can stand on its own after three to five years”. This is a reasonable sounding but misguided perception. Few if any programs or hubs are financially positive without constant subsidy. Consider the sentiment about self-sufficiency based on the timelines above when many programs and hubs in the system started, and the reality hits home even without the pandemic.

Universities are often at the front-end of the entrepreneur life cycle. Many founders may not directly associate their success with a university program, but the connections and culture in the university created by the programs contribute towards the founder success. The sentiment that “We create founders not startups” has been heard on more than one occasion in reference to university-driven programs.

There is a growing narrative that focuses on the future of engaging young people. A survey of year 12 students showed that 42 per cent had a ‘‘side hustle’’ that could generate income. An article in the Australian Financial Review noted that:

“while the young don’t have an exclusive lock on entrepreneurial innovation, there’s also a pretty inescapable link. There are the iconic American cases – 19-year-old Mark Zuckerberg starting Facebook, 20-year-old Bill Gates founding Microsoft, 30-year-old Jeff Bezos launching Amazon. But Australia has a similar story to tell. Gerry Harvey was 22 when he co-founded Harvey Norman, Frank Lowy 29 when he started Westfield, and Mike Cannon-Brookes and Scott Farquhar 23 when they created Atlassian.”

Look to any technology company touted as a success today and look at their founding date and the academic history of the founder. Many started around five to ten years ago and there is often a connection to university in their background. Again, anecdotal at best as we improve measurement approaches, but it is enough to understand that some form of support is needed now to create the success stories of tomorrow.

The system is changing – but the problem to solve remains

The innovation ecosystem is by nature a complex adaptive system. There is high uncertainty and it is constantly changing to adapt to rapid feedback. Institutions such as CEA that are larger, established, and sit outside the formal structure of the institution may be at greater risk when foundations of the system such as revenue models change.

But one thing that did not change is the reason why CEA exists. Indeed, the need is seen now more than ever. Australia was already slipping in global innovation indexes in absolute and relative terms. Support for entrepreneurs and innovation will be essential to build new capability and capacity.

The creative sector also requires increased support as one the most impacted sectors along with tourism and hospitality. Yet come of the greatest creative expressions emerge from collective suffering. There is a significant opportunity to mobilise the creative sector for both economic and social impact. Initiatives such as the $3,000 grant available for creative startup artists in Queensland are good, but the support of a healthy ecosystem will increase this investment by ensuring greater likelihood of successful and innovative use of the funds.

CEA is like most businesses, operating under one of three funding models: all funding from one, some funding from a few, or small funding from many. The funding model has shifted from a subsidiary outside the university to resources internal to the institution. It remains to be seen as to the extent that the programs will continue.

There is significant capability built up in the team that can be leveraged and the network that CEA created can still be mobilised. New structures of funding models can be created with perhaps reduced overheads and different funding sources. These new structures may or may not include the university. It would not be surprising to see other organisations and institutions that have a vested interest in the outcomes of creative innovation invest in the capability that has been built up among the team to fill the gap with different business models.

Reflecting back to our family business, traditional PCB manufacturing requires significant labour, chemicals, and multiple processes. Now, much of the process can be done through additive manufacturing at reduced cost and risk. What the innovation ecosystem looks like now is vastly different than what it was even five years ago. It will also change significantly as it evolves to a point five years from now.

I join with others in personally mourning and celebrating the great work performed and outcomes realised by the CEA team. But nature abhors a vacuum and there is significant opportunity for one or more organisations to fill the gap. I respect the current challenges we collectively share and difficulties that will be experience across many sectors including universities. I am also excited about what will inevitably come and the innovations that will happen both in the innovation ecosystem as well as the overall Australian community.

Disclaimer

I am a Research Fellow at QUT, Research Fellow (Innovation Ecosystems) at USQ, CEO of Startup Status, and Managing Director – Australia for the Global Entrepreneurship Network. Views expressed in this post are my own and do not represent these organisations. The aim from these posts is to inspire thought, prompt dialogue, and gain valuable feedback. Comments and conversation are always welcome.