The QODE Brisbane innovation and technology conference brought together innovators, startups, corporations, service providers, and government for two days of educating, showcasing, and collaborating on technology and innovation opportunities.

Vibhor Pandey and I had the opportunity to share reflections on the state of the Australian and Queensland innovation ecosystem. As much as you can prepare, there are points that invariably get cut or omitted in a 20-minute presentation.

Below is an overview on what was shared from the stage and further thoughts on what did not make it into the presentation.

Personal reflections: presenting at QODE

“The wisdom is in the room.”

Presenting at QODE was an honour, yet also daunting given the topic and audience. I have dedicated the last several years of my life in understanding and mapping the systems behind how entrepreneurs are supported in regions. Yet I am always learning something new, uncovering new areas of research, and meeting amazing people with deep knowledge in the topic.

To present on the state of anything, much less a broad topic of a national innovation ecosystem to a room full of other practitioners and researchers is humbling. There are many in the audience and those reading this post who can contribute to the topic of the “state of the innovation ecosystem”. As the saying goes, “the wisdom is in the room”. Your feedback and comments are welcome.

Gratitude goes to the QODE team including organiser Jackie Taranto and curator Gilad Grinbaum who helped frame and align the talk with the flow of the two-day conference. Also thanks to the many people with whom I tested ideas, the hundreds whose voices contribute to the presentation, and the thousands of entrepreneurs whose journeys are the reason why we do the work.

I co-presented the topic with a friend and colleague Vibhor Pandey who is mining deep data sets to gain a national perspective on entrepreneurial quality. His work with Queensland University of Technology and the MIT REAP program integrates well with my more qualitative research with the University of Southern Queensland into the role of innovation actors in building community resilience.

Vibhor and I considered several approaches leading up to the presentation, from promotional, critical, and academic. In the end, we set out to provide: what we knew of the state of the ecosystem from data and interview feedback, gaps in our understanding, and what work was being done to better understand and support those in the room. This was from different perspectives of traditional data mining and hearing from those in and out of the ecosystem.

Personal history and research

My journey to QODE began as most great things do in Seattle – in a garage.

When our family business began in the 70s, there were over 2,500 printed circuit board manufacturing companies in the United States. By the turn of the century when the company closed, there were only 250 manufacturers remaining due to technology advances and globalisation impacts.

The experience raised a few questions for me. What could you do with over 80 people who have been working and collaborating together, many of them for years? And what could we have done to mitigate or prepare for disruption in our industry? What connections would have provided support?

This experience framed my role decades later when I managed an innovation hub in Ipswich, Queensland, helping others to move into, or in some cases out of, their own garage. This began a deeper interest in the underlying system that supports entrepreneurs and led to my current PhD research and recent road tour of regions first in Queensland and soon across Australia.

Image credit: Anne-Marie Walton

The journey has seen me on the road for over 90 days over the past six months, with a solid stint from October to December 2018. The research has included over 170 interviews with stakeholders in regions including local government, entrepreneurs, innovation hubs, coworking spaces, economic development bodies, investors, service providers, community groups, and more – anyone involved in supporting early-stage entrepreneurs with high growth potential.

This background provides a frame for perspectives on the state of the innovation ecosystem.

A national and state perspective

Image credit: Leigh Staines

The Australian innovation ecosystem is emerging and diverse.

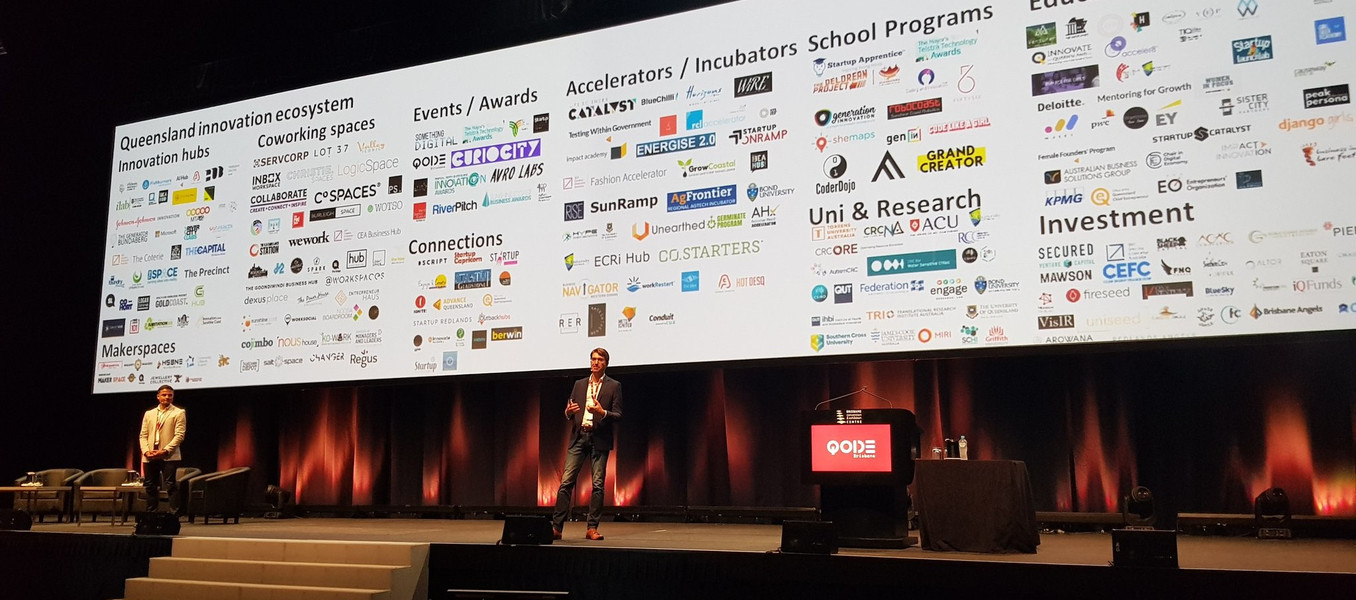

So what do we mean by the innovation ecosystem and what is the scale in Australia? The innovation ecosystem is the connection of those whose services support develop and deliver innovation outcomes in the nation. This is significant in Australia, with rapid growth in the number of coworking spaces, innovation hubs, makerspaces, investment groups, universities, connection groups, and others involved in supporting entrepreneurs. Queensland represents one part of this overall picture.

To keep track of the scope of the ecosystem, I am maintaining a public record at https://your.startupstatus.co/. We continue to work on engagement approaches to ensure this public record is as accurate as possible, even as the scope and scale constantly changes.

We are seeing increased specialisation in the Queensland ecosystem.

Similar to Australia, the Queensland innovation ecosystem has seen an explosion in recent years. Around half of the logos were not even on the map as of three years ago.

The “wall of logos” is a sample and not a full presentation, as there are many areas not displayed due to space or sheer volume of actors. These segments include community and networking groups, service providers, and corporations or firms involved in supporting new ventures. Like the innovation ecosystem it represents, the map will continue to evolve and expand.

The growth is seeing specialisation in several areas:

- Stage: Some aspects of the ecosystem focus on early stage, while others are emerging to emphasise later stage growth and scale.

- Industry: Entire segments of the ecosystem are focusing on different sectors, such as creative industries, agriculture, or resources and mining.

- Function: Programs and organisations emphasise functions of the entrepreneurial journey, such as cross-country collaboration, angel investment, or product development.

- Technology: Some organisations and ecosystem segments emphasise a specific technology, such as artificial intelligence, hardware, virtual reality, or blockchain.

- Community Segment: Some parts of the ecosystem have a dedicated focus on a community segment, such as female entrepreneurs, regional or rural entrepreneurs, indigenous entrepreneurs, or social enterprises.

There are some key takeaways from a high-level view of the recent growth and focus of the ecosystem. The ecosystem is young and emerging in maturity. Many of these organisations who are supporting entrepreneurs are “entrepreneurial” in themselves. Corporations, governments, and universities are learning not only how to develop new, flexible business models, but also how to work with each other in new, non-traditional and unstructured ways.

The networks and connections between each of the areas of the ecosystem – investors, accelerators, spaces, universities, etc. – are forming and strengthening. Actors within each area – innovation hubs, investment groups – are learning where each are positioned in relation to each other.

Image credit: Timothy Hui

Innovation ecosystems can be resistant change, require entrepreneurial leadership and capital, and can take a long time.

This “newness” of the ecosystem needs to be considered in light of three observations from ecosystem research. First, entrepreneurship rates and quality can be consistent over a long period of time. A comprehensive study in Germany found that the rate of entrepreneurship in a region can be consistent, meaning a region that produces high numbers of entrepreneurs can be more likely to produce entrepreneurs. Conversely, a region that has low rates of entrepreneurship can find it difficult to change the rate of new business creation. This relates to several factors, but deep cultural norms play a large part.

Second, vibrant entrepreneurial ecosystems are often correlated to the presence of what is known as recycled entrepreneurs. Simply creating policy frameworks or physical spaces, or bringing in third-party programs can be ineffective without practical experience and capital from those who have had success, exited, and give back to the local community.

Finally, innovation ecosystems can take a long time to produce outcomes. Many regions seem to emerge overnight. Looking into the history, you realise they began with policy decisions or a few leaders meeting consistently in a pub decades past. This creates a challenge for those wanting to replicate success, as they may copy the visible expression of an innovation hub or corporate program without understanding the cultural heritage that went into the foundations.

Measuring entrepreneurial quality

Data helps to measure entrepreneur quality in a region.

Innovation ecosystem, or more accurately entrepreneurial ecosystems, exist to produce quality entrepreneurs. This is an area that Vibhor has been exploring with the MIT Regional Entrepreneurship Acceleration Project (REAP) initiative.

Image credit: Kara Burns

Vibhor shared about the two attributes often used to measure entrepreneurial outcomes include Jobs and Growth. Both can be a challenge in definition and scope. Jobs can incorporate full-time, part-time, contract, interns, local, Australian, or off-shore positions. Finding accurate and timely data specific to impact on local economic outcomes from startup ventures can be difficult, particularly given the dynamic nature of new business entries and exits.

Image credit: Rowena Barett

The QUT LAB-ii project is designed to address this challenge, bringing in multiple data sets to better understand entrepreneurial quality. These include sources such as the Australian Business Register, IP Australia, export data, ASX, and other program and non-traditional sources. The framework provides an extensible platform for continuous improvement of data measurement capability.

Vibhor shared how these data sources allow for the development of an Entrepreneurial Quality Index, building on research by Stern and Guzman (2015), and Furman, Porter and Stern (2002). For example, entrepreneurial quality in a region can be determined by the number of new businesses that have a logo, trademark, patent, are exporting, or are listed on the ASX. Factors such as these have proven to be indicative of firm performance and provide an indication of entrepreneurial quality.

Image credit: Kara Burns

This quality index can then be mapped to specific regions down to post code and even street. The work being performed through the QUT’s MIT REAP project is allowing the data to indicate where entrepreneurs may have greater likelihood of success, which then provides valuable input into policy decisions across the nation.

The question remains, however, as to the correlation between the presence of innovation ecosystem actors and entrepreneurial quality. Vibor raised the question as to which comes first: Does an innovation ecosystem result in higher quality entrepreneurs, or do high quality entrepreneurs develop a high quality innovation ecosystem?

Perspectives from the innovation ecosystem

This provided a good segue into feedback from the 170 interviews conducted across the Queensland ecosystem from October 2018 to February 2019. I am still in the process of coding and analysing data, but I have analysed the content enough to extract themes from participant feedback.

Caveats and considerations

While not covered in the presentation, some caveats have been considered when putting this in writing:

First, this is a sample of feedback. We are working on a means to connect ecosystem outcomes with activity in a more accurate and timely manner. Until these measures are fully in place, interviews, surveys, and correlations with traditional data sets need to suffice. This is one sample of 170 interviews across 15 regions. There is always a desire for more, but this does provide one indication we can consider.

Second, this is expected to reflect Australia as much as Queensland. While the focus has been on Queensland, I have also conducted spot-visites into other metro areas including Melbourne, Darwin, Sydney, Adelaide, and Perth. The strengths and challenges are likely more reflective of stage of the ecosystem and an Australian cultural and economic historical influence rather than observations limited by state boundaries.

Third, the feedback does not necessarily reflect the “state” of the ecosystem. This is a reflection on feedback on those in and out of the ecosystem. The actual state of the ecosystem also includes the size, activity, economic performance, and more.

Finally, the feedback is on the functioning of the ecosystem, not national innovation policy. Recent headlines about innovation in the federal budget or tax and visa policy influence the system, but were not covered in the presentation.

Interview structure

The structure of the interviews followed a set format: What is working well, what are the challenges, what is the perspectives on the best possible outcome, and what would need to happen to realise that outcome? This feedback is then reviewed based on available data from the participant’s organisation, the region, and visible entrepreneurial activity.

The feedback has been broad, but a few themes are emerging. These themes are observable and identified by those who both participate in the ecosystem as well as those who observe the ecosystem but do not participate.

What is working well?

Community

Community can be strong in the innovation ecosystem.

Attributes of community include trust, shared outcomes, and support for each other’s activities without necessarily having any formal structure. This community is observed internal to an organisation such as an innovation hub or coworking space, within a geographic region, and across regions in a group such as innovation ecosystem leaders or industry groups.

Access

A primary benefit of the innovation ecosystem is access.

This includes access to technology, capital, new ideas, inspiration, information, new customers and markets, and professional services. The system as a whole acts as a hub, both physical and virtual, creating a node to provide new channels not available through other means.

Education

Education, or more specifically awareness, is a common shared positive attribute of the innovation ecosystem.

People not involved in the innovation ecosystem may not fully understand the functions performed by those supporting new businesses. However, most are aware and able to identify someone in their community who can support them in building, growing, and scaling new business ideas.

Leaders

In almost every region, there are leaders who support the development of local entrepreneurs.

Many of these leaders created spaces and programs well before top-down government programs were around. Many in the regions refer to these leaders as shaping local narratives, supporting new ways of thinking, and providing access across geographic and social boundaries.

What are the challenges?

Each of these positive reflections can be seen as having a challenging counterpart. There is strong community but this can also create exclusivity and in-crowds and out-crowds. The access is available but can also be limited by cultural barriers. There is awareness, but that is not necessarily translating into execution. Leaders are not necessarily sustainable and there are few plans for redundancy to back of a key individual.

Sustainability

Financial sustainability of the institutions and personal sustainability of individuals can be a challenge in innovation ecosystems.

The innovation ecosystem performs functions related to both economic development and community development portfolios. Early-stage organisations do not have sufficient funds to support the ecosystem on a fee-for-service basis, leaving it to corporations and established businesses, governments, and universities to fund activity.

Without self-seeding from venture capital returns, the ecosystem remains heavily subsidised. Actors across the ecosystems continue to explore various business models and configuration of funding approaches. In addition, funding organisations such as governments and corporations explore new forms of measurement to better account for their investment into innovation ecosystem activities.

Still, many leaders perform innovation ecosystem activities on a volunteer basis or in addition to their primary roles. Leader burnout can be a concern, particularly in areas where local awareness of the need is less prevalent.

Focus

“We cannot be all things to all people.”

This sentiment of not taking a generalist approach was shared in all regions I visited. The 2018 global Startup Genome report highlighted the need for regions to focus on core strengths to succeed when determining where to focus scarce resources. There may be individual hubs or programs that provide general entrepreneurial support, but there was a sense that the region overall needed to be known for something.

This focus needs to be more than simply agriculture, resources, or tourism. These are understandable from a national perspective, but a region such as Bundaberg or Rockhampton needs to understand how they differentiate. In Queensland, every region has great sunsets and many have strong capabilities in primary industries. The emphasis needs to be in more specific areas, while always being open for new opportunities. This is not at the expense of their neighbors but more a celebration and attraction of the individual region.

The theme of “Focus” also applies to finding the real problem to solve. All the activity in the ecosystem will not produce outcomes if the customer is not at the table with real problems being solved that someone is willing to pay for. These are often referred to as “moon shots”, or large goals that help focus the community’s attention and attract others from around the world who have a vested interest in solving the same challenges.

Collaboration

Having a focus on specialisation and moon shot challenges and making entrepreneurial support sustainable emphasises a need for greater collaboration.

Established organisations can take a “wait and see” perspective, can be tied to long internal decision cycles or procurement practices, or resist what can be seen as competing programs. Those who support entrepreneurs can emphasise quick action, operate with fewer governance frameworks, and attract a different and non-traditional cohort of business activity.

Add in well-established relationship hierarchies and political cycles, and collaboration can be a popular sentiment but not necessarily a naturally occurring phenomenon.

Culture

Culture is simply “the way we doing things around here.”

Feedback related to tall-poppy, fear of failure, and perspectives of us vs. them can be considered inherent to the Australian culture to the point of being cliche. The culture inherent to the innovation ecosystem can be seen as contrary to this sentiment, with its give-first and founder-first approaches. Yet the entrepreneurial ecosystem culture can be limited when embedded cultural perspectives isolate the impact to a closed community.

Two attributes related to culture that are being explored as a result of the research are value and trust. These two factors can be seen as critical for speed in the entrepreneurial journey. Entrepreneurs will move to the path of least resistance and lower transaction cost. Increasing trust and value increases the speed of engagement and opens more networks.

So what needs to happen?

With these considerations in mind, we briefly shared a few recommendations based on feedback, research, and work currently being done in Queensland and Australia. The recommendations were represented using an MIT REAP framework of Stakeholders, Strategy and System.

Stakeholders: Everyone around the table

Diversity and participation are key principles of effective innovation ecosystems. A new form of collaboration body may be needed to bring everyone around the table and align policy, services, support, finance, and local business activity. Adding more programs or providing lump-sum funding will have limited impact without first creating a context in which collaboration can happen. This requires more intentional work that is unique to each region.

Strategy: Focus on moon shots

Barriers to innovation ecosystem outcomes could be seen as being related to Australia’s unparalleled economic prosperity. Having it so good may have a downside of not providing a necessity to change. As such, a lack of collaboration and culture challenges might not be addressed with existential conversation about the nature of the innovation ecosystem. Rather, communities can be mobilised through solving real, shared problems, leverage strengths that make each region and group unique, and bringing everyone together to address these challenges.

System: Measurement and data

As the innovation ecosystem matures, we need reliable, timely, and accurate data to understand how we are performing and make better decisions. This includes improved access and use of traditional data sets as well as non-traditional data.

Current initiatives

Each of these areas are being addressed through a considered and structured approach. Vibhor shared about current initiatives framed using three perspectives of structure, human, and activation.

Structural interventions include the integration of data platforms and development of new data collection approaches, as well as underlying policy frameworks. Human approaches include cultural and collaborative frameworks, with a primary example being the MIT REAP program which brings together corporations, governments, entrepreneurs, investment, and others to mobilise a region’s entrepreneur capability around common challenges. Finally, Activation includes specific programs and events to execute on the work and provide feedback into the structure and human aspects.

A main point is that work is being done behind the scenes to support the exceptional work of those supporting the innovation ecosystem.

Final thoughts: Connect

Queensland, and Australia overall, is an emerging and rapidly expanding innovation ecosystem. There are many opportunities and a number of challenges. Our aim with the presentation was to provide an overview on a complex and dynamic system, while offering practical insights to leaders who want actionable outcomes.

Vibhor and I wrestled the one thing we might influence over the next 12 months. If we could see one change, what would it be? In our mind, that word was “connect“. It was a word repeated in most of the presentations through QODE – connect to technology, connect across regions, connect across business communities, connect with data. It is embedded into the Queensland MIT REAP mandate for “Queensland Connect”, and a main concept in the recent Advance Queensland draft strategy.

So what does this practically mean? The presentation provided three potential opportunities:

First, we can ask the question: “Who is not in the room?”Who else needs to be around the table who may not look or be like us or that we might disagree with, but who can bring a diverse perspective and new collaboration opportunities?

Second, how do we connect with challenges outside of our own perspective? This may mean connecting with people outside our region, our state, or Australia to participate in global conversations with local application.

Finally, how do we connect with data and the reality of the situation? This allows us to move beyond the loudest opinion and mitigate political influence to share successes and make more effective decisions.

The Australian innovation ecosystem is rapidly emerging with significant potential. While we can learn from other countries, we also need to acknowledge the Australian context. What is required is more than a new initiative, group, or program, but a way of engaging that makes the entrepreneur journey more effective.

If we connect to those not currently around the table, with challenges outside of ourselves, and with data for informed decisions, we can leverage the momentum and make significant progress.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks