“Over 5 million jobs face a high probability of being replaced in the next decade or two.”

~Nathan Taylor, CEDA Chief Economist

The JOB: the foundation of corporate productivity, the goal of academic curriculum, and the basis for professional identity. Employment comes with a job description, school prepares us for a career made up of jobs, and more often than not people introduce themselves as what they are paid to do.

The job, this lynchpin of our organisational psyche, is changing. Reports highlight the rapid replacement of jobs as we know them due to automation, disruptions, and the growing gig economy. Most analysts say that technology has created more jobs than it has destroyed. This can be little comfort to those who discover their 30-year career investment has been in a job that is deemed to be “dangerous, dull, and boring”.

Smart grids and home energy battery storage are reducing demand on electrical transmission poles and wires that were built to last decades. Automation is replacing traditional manufacturing. Social media and bloggers are changing the role of the news journalist. As these jobs go away or are morphed into something new, entire supply chains are impacted as revenue streams shift.

All of this results in sensational headlines and a predictable fear-based response. Terms such as “disruptive innovation” are spoken of with either excitement (for those disrupting) or annoyance (to those being disrupted). A common sentiment I hear from professionals in their 50s and 60s is that:

“My profession is ending a decade before my career. What do I do?”

Insight into the 11th Grade perspective

I recently attended a Future Thinking presentation put on by the Queensland University of Technology Real World Futures program as part of the Vice-Chancellor’s STEM camp for Year 11 students. The keynote speaker for the session was Roger Lawrence, Chief Technologist, Innovation for HP, Asia Pacific & Japan and Chair of the Australian Information Industry Association (AIIA).

Roger shared his perspective on shifts in technology and jobs he believed would be required to support these shifts. One of the most interesting observations was the role of the ethicist, popularised in the questions as how a driverless car decides who lives or dies in a decision-making process.

What impacted me the most, however, was the Q&A time at the end of the session. My experience with the Q&A portion of many corporate presentations I attend is that there is usually a bit of hesitant silence interjected by well-crafted questions from a few industry experts. By comparison, the Q&A session with the Grade 11s in attendance was rapid-fire, relevant, articulate, and fearless.

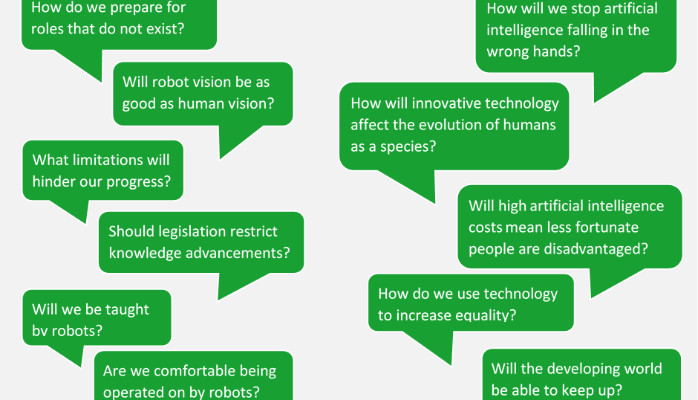

In addition to the questions from the floor, the session incorporated technology using GoSoapBox that allowed the audience to submit questions via the app. The Real World Futures facilitators were kind enough to send me a copy of the questions submitted:

- What limitations will hinder the progression of future technology?

- As more robots with vision sensing are being developed, how close can we get robot vision to human vision?

- Due to the increase in need for education, will teaching be done by human teachers or robots and will it be in schools or at home via virtual education

- If artificial intelligence is introduced to the public, such as the tutor, what would the cost be for this artificial intelligence? And are less fortunate people disadvantaged by these costs?

- How do you think the innovative technology will affect the evolution of humans as a species?

- Because most of the STEM Industries are constantly changing and adapting, most of the jobs we will have do not exist yet. How do you advise we prepare for these roles that don’t yet exist?

- In your visions for the next 10 years, there were images of people in theatre being operated on by robotic arms. My question is thus; how easily will general society adjust to the idea of being operated on by super-efficient cold blooded robots as opposed to humans, flawed but ethical? Do you think this is something that people will ever feel comfortable with?

- How far should legislation restrict STEM advancements?

- As technology advances and is rolled out further and further, will the 3rd world” be able to keep up with the Western (more technologically advanced) world?

- Where do you see cryptocurrencies in 10 years?

- Is there really any benefit to having robots? Will having robots mean there will be less jobs available to each person because of these new robots?

- How will we stop artificial intelligence falling into the wrong hands, such as countries which do not have strict legislation in regards to ethics?

- I’m interested in hearing what impact there will be on the languages used around the world?

- How can we utilise our future technological ability to increase equality within our society?

The questions prompted the adults around me to note the insight and maturity of the students. The energy in the room came from questions born out of curiosity rather than questions based in self-interest or fear. As I mentally compared the future leaders in the room to leaders a few generations ahead, I reminded myself about how short a time span we have before we are consumed by society’s constraints.

Channelling the postmodern perspective

Each teenage generation is characterised by what can be considered a postmodern perspective. It is the hallmark of the new generation, regardless of the era. The randomness of James Dean staring at a monkey in the 50’s “Rebel Without a Cause” is the same rebellion against conformity characterised by a group of teens decades later in the 80’s “The Breakfast Club”.

Postmodernism simply refers to a perspective that challenges the modern perspective. This is explained with three characteristics:

1. Deconstruction

The postmodern perspective takes little at face value. Nothing is sacred. Language, morals, political and economic systems, religion, technologies, and social norms are all defined as grand narratives to be deconstructed into their smallest component pieces. For upcoming generations, this is a necessary and exciting process of understanding how things work. For the incumbent generation who has just started to made sense of things, it can be a threatening process.

2. Dialogue

This deconstruction occurs within a dialogue, a conversation that incorporates art, activism, and interaction. Sense is made of the situation based on the interaction between the upcoming generation and the established order. The process of asking the question is as important as the answer.

3. Relative

This deconstruction and dialogue all occurs from a perspective relative to the individual. The upcoming generation can be criticised as being selfish and entitled. But how do we reconcile this with statements about the same generation being the most sustainably conscious generation ever?

The answer I believe is not that upcoming generations fail to care about others. Rather, they do not care about what society tells them they need to care about. They do not necessarily care about making profit for your corporation, having a job in a career you define for them, or using technology the way you say it should be used.

The upcoming generation needs you to help them make sense of the world, but they will tell you what that means to them. This will likely not be the same as what it means to you.

Where we can make a difference

What one generation considers to be disruptive, another sees as business as usual. As I was discussing this post with a colleague, he shared with me a story about his 10 year old brother. The young boy could not comprehend why he could not call his mom when she was on a plane. We need to capture that sense of ridiculousness when staring at business as usual in order to ensure in a decade that this same 10 year old is designing instant communication systems for anywhere-anytime access.

We have a short span of time before the upcoming generation accept the constraints of the world to create a new modern order.

A principal in a progressive local school said to me to the effect, “Chad, if we can figure out how to keep that perspective, then we have a chance of making a real difference.” It is a challenge I believe that is worth committing my life towards. We want young people to look at challenges such as climate change, systemic inequality, embedded poverty, terrorism, domestic violence, and chronic substance abuse with the same incredulousness as a 10 year old not understanding why he can’t call his mom on a plane.

Why, with centuries of so many technological advances, have we proven incapable of addressing such systemic challenges? I do not want the next generation to accept whatever answer the current establishment has created for itself.

I want the next generation to deconstruct our response, to ask the challenging question through dialogue, and come up with a response that means something to them. Because I and my generation will be gone before long, and they will be the ones left taking care of the place for those who come after.

Rather than telling the next generation about your disruptive innovation, what would it look like to engage them in a conversation where they tell you what that innovation means? And how do we help guide the conversation towards a meaning that makes a lasting improvement for humanity? I believe that is a conversation worth having.