There is increasing support for female entrepreneurs in Australia. The trend of women starting their own businesses is growing and by all indications will continue to grow. The result is a an environment that is good for female founders and for the surrounding economies and communities that support them.

As part of a review of the current state of support for female entrepreneurship in Australia, we aim the Startup Status map at those who specifically focus their efforts on developing and supporting females who create early-stage businesses and projects with potential for high growth.

Like previous mapping exercises, there are a few caveats:

- We begin with a discussion about why female entrepreneurship matters. There is a gender imbalance in terms of economic opportunities. This imbalance is resistant to change due to embedded and systemic constraints and norms. Entrepreneurship provides a key opportunity to address gender gaps in society as well as provide greater economic prosperity. We believe this is important.

- The scope is the innovation ecosystem, or those who support for early stage entrepreneurs with high-growth potential. The lines blur when focusing on a subset of the ecosystem. For example, there are many women’s networking groups that support women in business. Other groups exist for specialised industries such as female legal or agriculture communities. A distinction is made on those who directly support female entrepreneurs, but this distinction is not always clear.

- This is not complete, but we aim for comprehensive. The map is based on personal networks and research. Some groups will be missed, particularly at the local level. Please provide feedback through the feedback form if there are actors supporting female entrepreneurs in Australia that are not included on the current map.

- The categories in the map are subjective and open to interpretation. Feedback is welcome.

A review of the need to support female entrepreneurs

We begin with understanding why we are having this conversation in the first place. In 2012, I posted about wage inequality in Australia as part of a research paper. The research project outlined embedded and systemic factors behind gender imbalance, including: wage differences by industry sector, industry gender bias and earning potential, how caring for older and younger dependents impacts female employment participation rates, and financial resilience related to retirement savings.

The intent is not to refresh the research as the challenge is largely known. Most popular news sites such as Smart Company, Inc., or Forbes have posts that outline female entrepreneurship statistics. My personal reasons for mapping and sharing is to understand how the innovation ecosystem supports community resilience, and gender is a factor.

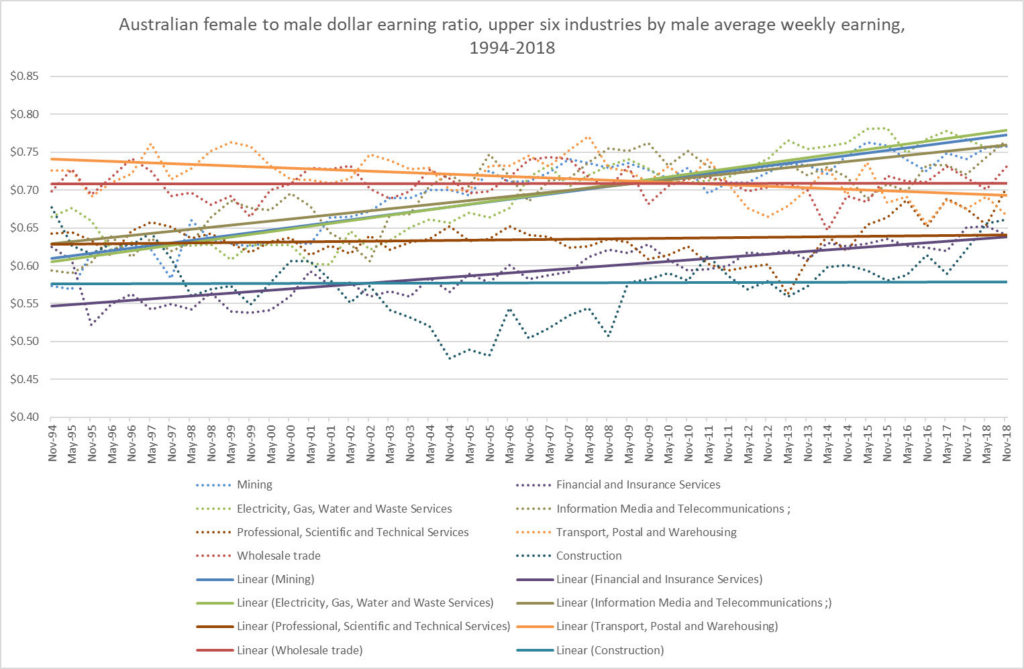

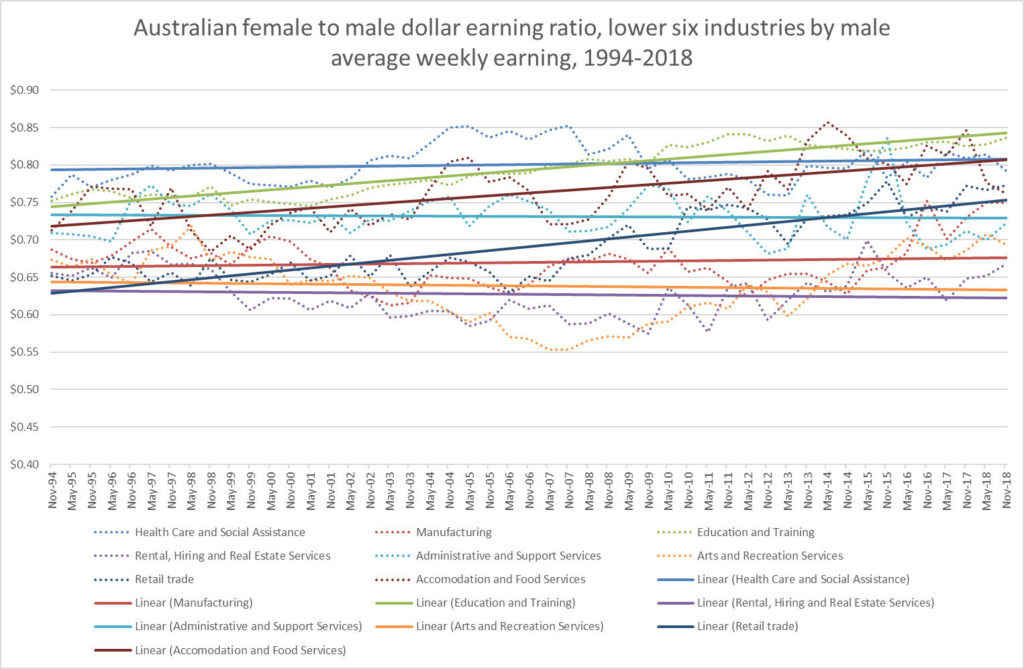

An indicator often cited is the wage gap between males and females. On average, females make $0.73 on the male dollar. This varies based on industry sector, with a low of $0.64 in financial services and a high of $0.84 in Education and Training. This number is based on the ABS average weekly earnings by gender and industry.

Some sectors have been fairly resilient to change. The wage gap for females in financial services closed by 3% ($0.62 to $0.64) between 1994 and 2018 and the wage gap in the construction sector increased by 2% ($0.68 to $0.66). Other sectors significantly closed the gap such as mining by 32% ($0.57 to $0.76) and ICT by 29% ($0.59 to $0.77). These are averages and generalisations, as there are significant fluctuations over time and variances within sub-sectors of an industry sector.

The important take-away is the comparative trend between sectors over a longer period of time. The earning potential of a given industry is also a consideration. Sectors such as education that have greater parity and have a higher representation of females, yet looking deeper the sector pay gap remains due to more males being in higher paying leadership roles.

There is a common misconception that wage inequality compares like-for-like individuals in similar positions. While same-position pay differences are still evident in some industries and pay levels, the gap is largely attributed to lower representation of females in senior positions. The AICD recently reported a 29.7% representation of females on ASX 200 boards. A Chief Executive Women 2018 Census report noted that females represented 34% of functional roles, 12.3% of line roles, 12% CFO positions and 7% CEO positions.

A common attributable factor is the greater likelihood of women to stay at home with children, care for elderly dependents, and to be financially responsible in single-parent situations. The statistics I noted in my 2012 post were that 50% of mothers are out of the workforce if their youngest child is under two years old. The lack of employment continues for almost 33% of mothers whose youngest child is between five and 11 years of age.

More senior job roles often require flexibility for international travel and long hours. This makes it difficult to compete for position when also caring for dependents. The continued lower earning potential then creates an embedded cycle that impacts on long-term savings and future career and financial investment opportunities.

A reflection of the need for flexibility can be seen in labour force participation rates in industry by employment status (full-time versus part-time). Females have greater representation in part time roles across industries, likely attributable to the need for flexibility and re-entry from being out of the workforce. An exception to this is health care and education, industries which may allow for greater flexibility.

The numbers also do not reflect roles within the industry. When I performed the analysis in 2012, 22% of the ICT sector was female, but over 60% of the females were in roles related to client support, administrative, or project management. There is potential to achieve gender balance in a workplace but still have inequality due to the roles available due to structure of the job.

Which brings us to the potential of entrepreneurship to provide opportunity for all. This is particularly of note in the area of startups, or early stage companies with high growth potential. Startups can be considered an equaliser – providing anyone an opportunity to build, grow, and scale their business.

The difference in female entrepreneurs

Female startup founders have similar under-representation in the startup sector as they do in other industry sectors. Of founders who responded to the 2018 Startup Muster survey, 22.3% identified as female. Berger and Kuckertz outlined the 2015 Startup Genome city-based startup survey to show female respondent representation ranging from 9% to 30%, with Sydney at 14%. Victoria’s Launchvic 2018 startup ecosystem report noted 28% of founders as female.

These numbers can be seen as roughly consistent with investment into female founder companies. Crunchbase reported around 20% of 2018’s venture funding went into companies with at least female founder, although this drops to 12% when removing a $14 billion outlier round. The number drops further to 4% when considering only female founding teams.

Gender plays a significant role in the identity of an entrepreneur, which I encountered in my own research across Australia. A single mom in a regional area questioned whether she would be able to take advantage of a city-based accelerator that required on-site attendance over 3 months. A male entrepreneur was doing whatever it took to have his one shot at starting a business while his wife looked after the kids. These anecdotal stories align with a UK-based four-decade labour force review that showed that unemployment increases likelihood to self-employ in men while divorce lowers the likelihood to self-employ in women.

These social factors reflect that the gender gap is not due to capability. Berger and Kuckertz analysed data from 4,928 forms in the United States. When comparing like-for-like (hours worked, age of business, industry, firm size, company structure, education, and prior experience), gender does not influence the survivability or performance of a firm.

Yet no situation is equal. There are strong opposing and promoting forces for female entrepreneurs. On the one hand, males work longer hours, are more dominant in higher-paying industry sectors and across senior roles, and can accrue more career experience without filling a carer role. On the other hand, females as a population are more educated, smarter, and resilient.

In the Berger and Kuckertz analysis of female entrepreneurship across startup ecosystems, they noted that a positive appraisal of local government related to a higher proportion of male founders, and male representation is lower where there is a negative appraisal of local government. It is not that women start a business because they disapprove of local government, but in spite of it. The inference is that women are more likely to found businesses in a challenging environment. Women have a different approach in regards to risk, networks, access to resources, success, and reactions to government support.

This propensity is a good thing, particularly for regional Australia. The approach to female entrepreneurship is different in metro versus regional rural, and remote areas. In regional areas experiencing factors of depopulation, masculinization, and aging, there is a greater emphasis for female entrepreneurs to access networks and engage with online trading. They are also better positioned to help a region diversify outside of the primary traditional sectors of agriculture that are more likely to be managed by a primary male earner.

Australian sources of support

Support for female entrepreneurs comes from several areas of society. In 2016 / 2017, large consultancies provided dedicated research outlining the challenges and opportunities for female entrepreneurs, including:

- Deloitte’s Women entrepreneurs: Developing collaborative ecosystems for success (2016)

- PwC’s Women unbound: Unleashing female entrepreneur potential (2017)

- KPMG’s Women Entrepreneurs: Passion, Purpose and Perseverance (2016)

Banks are also involved, with programs including Westpac’s Women in Tech and Ruby Connections platform, CommBank’s Women in Focus, NAB supporting female-focused investment firm Scale through the bank’s JBWere investment arm, and ANZ partnering with female-focused, BlueChilli powered accelerator program SheStarts. Universities run dedicated programs for both technical skills and entrepreneurship, including University of Queensland’s Women in Engineering, University of Technology Sydney’s Women in Venture speaking series, Swinburne’s Standing out from the Crowd program, Queensland University of Technology’s HerHub, and University of Southern Queensland’s regional female entrepreneurship WiRE program.

Governments are also involved for the economic and community outcomes. Examples include the Federal Boosting Female Founders initiative, the NSW government’s female entrepreneur fact sheet (2016) and Women Entrepreneur’s Network, Advance Queensland’s Female Founders program, Tasmania’s Women in Tasmania page and 2018-2021 Strategy consultation report, and Victoria’s LaunchVic investment into the Girl Geek Academy program and Bright Sparks program. We can expect additional programs to emerge as policy focuses on supporting female entrepreneurs.

This support helps mobilise activity across Australia to create a dedicated ecosystem for female entrepreneurs looking to build, grow, and scale their business.

The Australian innovation ecosystem focused on female entrepreneurs

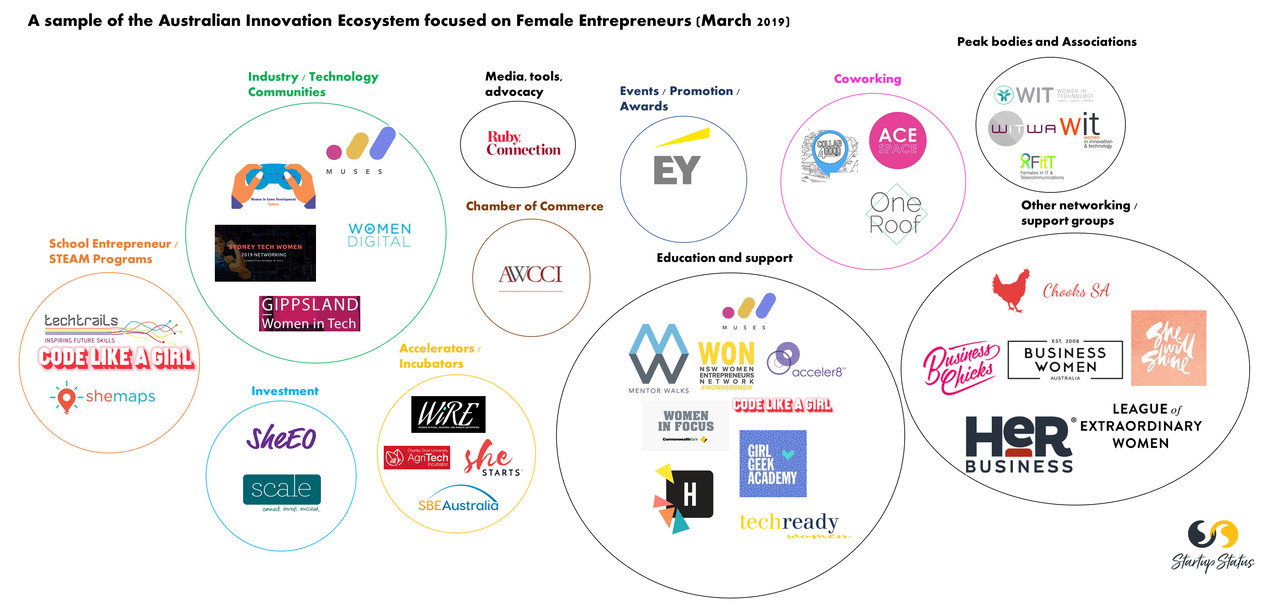

The outcome from my 2012 review on gender equality literature was that there were three dominant recommendations for change: Creating priming agents as examples for change; Engaging industry for education and awareness; and building in flexibility into roles and company structures. The organisations outlined in the map below can be seen to be addressing all of these areas.

The Startup Status map of the Australian innovation ecosystem contains over 1,500 organisations supporting early-stage, high growth potential entrepreneurs. We have reviewed these for those that have a specific focus on female entrepreneurs, as well as conducted a brief online review to include additional organisations. You can view the map here.

There will be others that we have missed. If you know of missing organisations you feel should be on the map please let us know through the feedback form. The map below is an example, as the information is constantly evolving and will likely change 10 minutes after we hit publish.

A summary of programs is below:

Accelerator programs

Some of the accelerator programs that focus on female entrepreneurs include USQ’s regional-focused WiRE program, Charles Sturt University’s Agritech incubator in Wagga Wagga, SBE Australia in Sydney, and BlueChilli’s SheStarts.

Industry / Technology Communities

Industry and technology communities focus on building technical skills in females. Examples include the Muses coding program, the multi-location Women in Digital groups, Sydney Tech Women, Women in Game Development, and Gippsland Women in Tech. Other groups could be in this category such as women networking and advocacy groups that support construction, legal, or agriculture sectors, but the map then begins to lose the innovation and entrepreneur focus.

School Entrepreneur / STEAM Programs

Addressing greater participation for female entrepreneurs and technologists is a generational challenge that starts in the hearts and minds of the next generation. This is the aim of targeted programs for female youth including Techtrails, Code Like A Girl, and SheMaps.

Coworking spaces

One of the barriers to engaging in entrepreneurial communities is the perception of a male-dominated boy’s club, even in coworking spaces. A few dedicated female-focused spaces have emerged. There have been a few attempts to include child-care with coworking spaces, with limited success. Feedback in speaking with owners of these spaces has been difficulties from creating additional complexity on an already challenging business model for a niche audience.

Examples of female-focused spaces include Adelaide’s Collab4Good and Melbourne’s Ace Space and One Roof Melbourne.

Education and support

The broad education and support organisations provide programs and support specific to female entrepreneurs. They can offer mentoring, training programs on topics such as financial literacy, and programing. These are different than more general communities but can also provide these communities. They are also different to other networking groups that are often membership-based.

Examples include Mentor Walks Australia, Acceler8 for financial literacy, technical programs of TechReady, Code like a Girl, Muses, and Girl Geek Academy, the NSW Women’s Entrepreneur Network, Women in Focus, and QUT’s HerHub.

Investment

Dedicated investment programs focus on female entrepreneurs include the SheEO program, which recently entered Australia, and Scale Investors.

Media, tools, advocacy

There are many websites focused on supporting women. Westpac’s Ruby Connection is one example listed.

Events / Pitch award programs

Events and award programs specific to female entrepreneurs help create the examples for others to follow and change the narrative. EY’s Entrepreneurial Winning Women is one example of this.

Chamber of Commerce

A Chamber of Commerce is a specific type of member-based organisation designed to advocate and focus effort towards an outcome. The Australian Women Chamber of Commerce does this for women in business.

Industry associations and peak bodies

Other industry associations and peak bodies focus on women in technical fields. These are more than an industry or technology community and more focused than a general networking group. Examples include Women in Technology, Women in Technology WA, Women in Innovation SA, and Females in IT and Telecommunication.

Other network / support groups

There is a growing list of female-focused networking groups, many of which also apply to entrepreneurs. Lists of these networking sites can be found on sites such as woman.com.auand CP Communications. Examples such as Women’s Network Australia provide generalist functions, whereas others appear to focus more on female entrepreneurs: Chooks SA, Business CHicks, Business Women Australia, Her Business, League of Extraordinary Women, and She Will Shine.

Closing the gap

Current estimates for gender pay equality are around 80 years in Australia and between 100 years to 170 years globally. There is some debate, even within female networks, about whether a dedicated focus on females creates a perception that women need extra support. Yet if nothing intentional and specific is done, then nothing will change.

Even this process of mapping and highlighting the activity is aimed at collectively highlighting and promoting the activity. The aim is also to identify those who are supporting entrepreneurs in Australia so we can collectively support more people, better.

With that in mind, please feel free to connect, share, and collaborate where you see value.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks